Prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is one of the most common forms of cancer in men, and the second most deadly cancer in Europe and the United States, behind lung cancer. Prostate cancer is usually an affliction of the older population and early symptoms tend to be quite mild. But because of this, they are easily ignored meaning that prostate cancer may only be detected at a later, more deadly, stage, with a higher possibility of metastasis to bone, lung, liver and elsewhere.

While prevention is key to stopping the disease, research is important to improve ways of treating prostate cancers at all its stages. Growing cancer in animals to model the disease has been – and still is – crucial for studying prostate carcinogenesis and testing new anticancer drugs.

Animal models for prostate cancer

The ideal animal model for prostate cancer should effectively simulate the occurrence, development, metastasis and pathophysiological changes of human prostate cancer. At present, mouse models, rat models and then dog models are used. To model prostate cancer in these animals, transgene, gene knockout and xenotransplantation is usually used. Prostate cancer animal models, especially models established by surgical or genetic ways, are one of the important platforms for prostate cancer research.

These models have proved to be very valuable in expanding our knowledge of the disease, but like many models, they do not simulate all the characteristics of human prostate cancer. Challenges to the use of animal models for the study of human prostate cancer include the significant anatomical differences that exist between species.

For the time being, no single model fully contains all the molecular changes and pathological events in the progression of human disease. Each model may only represent a specific pathological stage and has its own advantages and disadvantages in their similarity to the human disease, including structure and behaviour. As such, there is not yet a standard model used for a range of studies. Researchers choose the most suitable model according to the needs of their research.

Mouse model

Important information about prostate development and homeostasis was obtained by studying the development in animals, especially mice. However, the mouse prostate is different from the humans. The rodent prostate contains four different segments: dorsal lobe, ventral lobe, lateral lobe and anterior lobe, which surrounds the urethra. The dorsolateral lobe has the highest correlation with the peripheral zone of the human prostate. But unlike the rodent prostate, the human prostate does not have obvious lobular tissue. It does however have a similar regional structure and separation as rodent prostate, and prostate tumors usually originate in the peripheral area. These similarities, added to the genetic relatedness, the ease to generate mouse genetic models and the low cost of the models, have made mouse models the most widely used model for prostate cancer.

Rat model

Rats are one of the few species that spontaneously develop prostate adenocarcinomas. Compared to mice, the advantages of rats is that the volume of their prostate is significantly larger. The most widely used rat models are spontaneous models, chemically or hormonally-induced models, tumor cell line implantation models and genetic engineering models.

Canine model

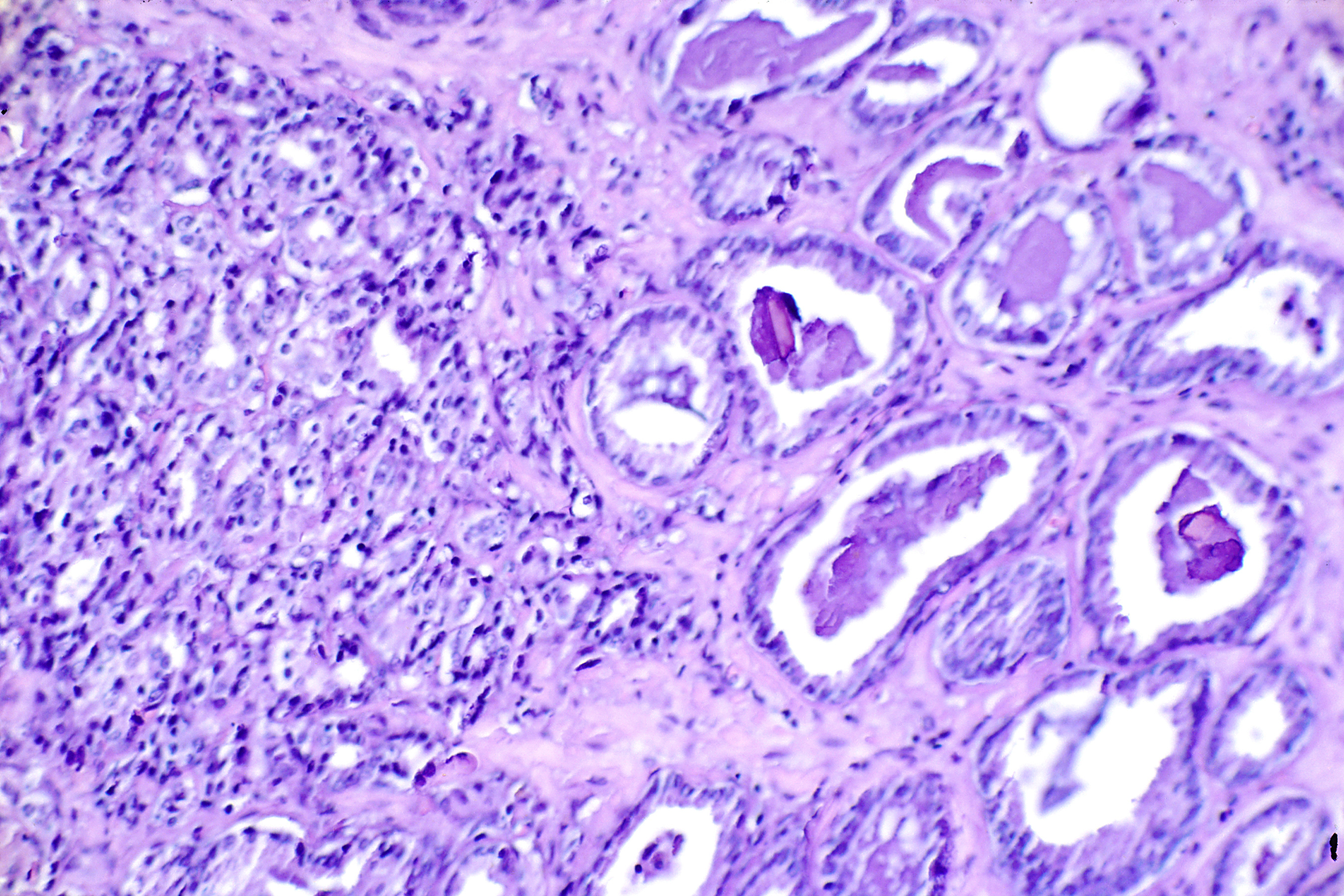

Other than humans, prostate cancer only naturally occurs in significant numbers in dogs. While the cancer in dogs shares characteristics with humans - dogs have a single-lobed prostate gland (like humans) but without the anatomic regions seen in the human prostate - there are differences in the likelihood of the cancer metastasizing and the tissue of the prostate1. Canine prostate cancer is a malignant epithelial tumor, with human-like Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) foci, cystic gonadal dilatation, and obvious suppurative and lymphocytic inflammation, so it is usually classified as an adenocarcinoma. Due to the high metastasis of canine prostate cancer, most dogs develop advanced diseases with local invasion and extensive visceral metastasis. At present, the two commonly used models are spontaneous and tumor cell line transplantation in dogs.

Alternative models

While animal models are used for the study of prostate cancer, alternative models and methods are increasingly being considered to replace, or at least reduce, the number of animals used in this particular field of research. Among these there are mathematical models; 2-D and 3-D cell cultures; microfluidic devices; the chicken egg chorioallantoic membrane-based model; and zebrafish embryo-based models. Immortalised cell lines still seem to be the most commonly used models in the field of prostate cancer research. In the future, technological advances will help build more effective cell culture systems, such as 3-D cultures or organ-on-a-chip devices, that will further decrease the need to use animals in the pursuit to fight prostate cancer

Major discoveries

It was notably studies in dogs that helped Charles Huggins discover that the growth of prostate tumours was dependant on the natural hormones of the body. He found that reducing male sex hormones or increasing female hormones could treat prostate cancer. Even patients with only a short time to live showed improvement from this new type of treatment, which had fewer side effects than other therapies. For his groundbreaking work and the treatments he helped to develop, Charles Huggins was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1966.

In line with this newfound knowledge, scientists in the 1980s discovered that an anti-fungal drug could stop cells making testosterone – the hormone that drives prostate cancer growth. But this drug had to be taken several times a day and it had serious side effects. Researchers went on to develop an alternative, a drug called abiraterone. Mice given abiraterone once a day for two weeks had virtually no testosterone in their blood, with only slight side effects. Thanks to this work in mice, the drug went on into clinical trials and is now available to men with advanced prostate cancer.

Cancer models in mice were also used to develop Cabozantinib, a drug that targets two mechanisms that cancer cells use to survive2. By blocking VEGF receptors on the surface of the cells, the cancer cells are starved of oxygen but this leads to them migrating to a new area and spreading through the body. By targeting another receptor (c-MET) as well, Cabozantinib prevents the spreading and reduces the ability of the cancer to grow. In tests on 108 men with prostate cancer that had spread to bone, which is usually untreatable, the tumours grew in just 3 of them and two-thirds reported less pain.

Rodent studies of the drug goserelin, originally being investigated as a possible fertility treatment, showed that it suppresses the body's release of hormones that increase prostate tumour growth3. This effect was unexpected and was unlikely to have been recognised except through experiments on animals. Further animal studies were needed to work out the best way for people to be given this medicine, since it is inactivated in the stomach when taken by mouth. A long-lasting injection, which gradually releases the medicine over 28 days, was developed in rats. As a result of this research, not only has an effective medicine against prostate cancer been developed, but also an important new drug delivery system.

Animal models of prostate cancer have helped and will continue to help researchers reveal the pathogenesis, disease progression and uncover the mystery of invasion and metastasis of prostate cancer.

References

- http://www.hindawi.com/journals/pc/2011/895238/

- http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn21516-new-cancer-drug-sabotages-tumours-escape-route.html

- The Ethics of Research Involving Animals, Nuffield Council on Bioethics

- https://meddocsonline.org/journal-of-veterinary-medicine-and-animal-sciences/the-current-status-of-prostate-cancer-animal-models.pdf

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0261192920929701?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub++0pubmed&

Last edited: 15 June 2022 11:26