Heart transplants successful in humans

The transplantation of major organs depends on the ability to join blood vessels. An effective method was developed by Alexis CarrelANCHOR using cats and dogs, and for this he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1912. Carrel also experimented with kidney transplants, and succeeded in removing and transplanting a kidney to a different site in the same animal.ANCHOR He found that a kidney transplanted from a different animal ceased to work after a few days. He therefore concluded that although the surgery worked well, other factors in the host caused changes to the kidney grafted from another animal. He was probably the first person to uncover the phenomenon of rejection, which was confirmed in 1923 by rather more sophisticated experiments by WilliamsonANCHOR in dogs.

The transplantation of major organs depends on the ability to join blood vessels. An effective method was developed by Alexis CarrelANCHOR using cats and dogs, and for this he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1912. Carrel also experimented with kidney transplants, and succeeded in removing and transplanting a kidney to a different site in the same animal.ANCHOR He found that a kidney transplanted from a different animal ceased to work after a few days. He therefore concluded that although the surgery worked well, other factors in the host caused changes to the kidney grafted from another animal. He was probably the first person to uncover the phenomenon of rejection, which was confirmed in 1923 by rather more sophisticated experiments by WilliamsonANCHOR in dogs.

Overcoming rejection

Heart transplants in dogs

Human heart transplants

Further developments

References

Overcoming rejection

The first kidney transplants leading to long-term survival were performed on dogs in the 1950s, following perfection of the surgery by Dr Joseph Murray.ANCHOR He also carried out the first human kidney transplantANCHOR, between identical twins, in 1954. However, the problem of rejection of grafts from genetically different donors was yet to be overcome. Knowledge about the immunological basis of rejection, the development of tolerance, and ultimately the development of immunosuppressant drugs came from extensive research on animals from the 1950s onwards. The genetic basis of tissue typing, which ensures the best long-term survival of grafts, was also worked out using animals, by Peter Gorer and George Snell using inbred strains of mice, in 1965.ANCHOR Five Nobel prizes (Alexis Carrel in 1912, Peter Medawar in 1960, George Snell in 1980, George Hitchings in 1988, Joseph Murray in 1990) were awarded for different aspects of research that has assisted the success of transplantation.

Heart transplants in dogs

Norman Shumway and Richard Lower in San Francisco, Adrian Kantrowitz in New York and Christiaan Barnard in South Africa all investigated the possibility of heart transplantation through research on dogs. The transplant procedure in dogs was first attempted by Shumway and Lower in 1958, and was fully developed in 1961. By 1967, after ten years of research, many of the dogs could be returned to full health following the surgery, surviving for a year or more.

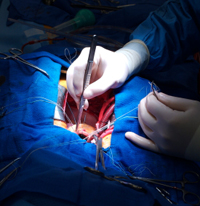

Human heart transplants

The first successful human heart transplant was famously performed by the South African surgeon Christiaan Barnard on 3rd December 1967, while the American teams were still preparing to move their work into humans. The heart which was replaced belonged to 53-year-old Louis Washkansky, a patient with severe heart failure and only a short time to live. Unfortunately Washkansky died from pneumonia 18 days after the operation. The immunosuppressant drugs which were needed for the body to accept the new heart, lowered his resistance to infection critically, although the new heart continued to beat strongly.

By January 1968 a further four heart transplants had been carried out by Kantrowitz and Shumway in the USA, but the recipients only survived for a short while before succumbing to infections. Between 1968 and 1970 many cardiac surgeons with little knowledge of immunology, and without prior experience of the procedure in dogs attempted to perform transplants. All of the recipients of these early transplants died within a couple of months, either from rejection or infection.

Further developments

Continuing with their research, Shumway and Lower developed a successful technique in 1970,ANCHOR which led to heart transplants becoming a routine procedure. This, combined with advances in immunosuppressant drugs, meant that by the 1980’s transplant rejection could be controlled more successfully. By 1980, after 12 years of further research, 65% of heart transplant patients survived for more than a year following surgery. Thousands of heart transplants are now carried out every year, and 95% of people who receive heart transplants survive for more than five years. Work is still continuing on transplants to find new sources of donor organs, and to find new ways of increasing the life expectancy of transplant patients.

Kantrowitz went on to develop a ventricular assist device (VAD), an artificial pump which helps to relieve strain on a failing heart by taking up some of its function. A VAD can help patients who are waiting for a heart transplant, and can delay the need for a transplant by up to 15 years.ANCHOR

References

- Carrel A (1912) Surg Gynec Obst 14, 246

- Carrel A (1910) J Exper Med 14, 146

- Williamson C (1926) J Urol 16, 231

- Moore F (1964) Give and Take: the Development of Tissue Transplantation, Saunders, New York

- Mitka, M. (2001) J Am Med Assoc 286.21: 2661

- Brent L & Sells R (1989) in Organ Transplantation, Current Clinical and Immunological Concepts

- Dong,E., Griepp,R.B., Stinson,E.B., Shumway,N.E. (1972) Clinical Transplantation of the Heart. Ann. Surg. 176: 503

- Mitka, M. (2001) J Am Med Assoc 286.21: 2661

Last edited: 3 November 2014 16:47