The 'organiser effect' in embryonic development

Studying the eggs of frogs and newts, Spemann observed their development following fertilisation. The first divisions of the egg cell had been studied before. It forms a hollow sphere, and after several divisions the sphere’s walls consist of three layers of cells - ectoderm, mesoderm and entoderm. The space inside is called the blastophore. The brain and spinal cord arise from the ectoderm, the mesoderm forms the skeleton and muscles and the entoderm forms the digestive system.

Studying the eggs of frogs and newts, Spemann observed their development following fertilisation. The first divisions of the egg cell had been studied before. It forms a hollow sphere, and after several divisions the sphere’s walls consist of three layers of cells - ectoderm, mesoderm and entoderm. The space inside is called the blastophore. The brain and spinal cord arise from the ectoderm, the mesoderm forms the skeleton and muscles and the entoderm forms the digestive system.

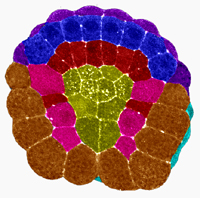

To discover how these processes were controlled Spemann used the different coloured eggs of several animal species, transplanting tissue from one to another during development. He discovered that the cells destined to become skin could develop into nervous tissue if they were transplanted into a region where the spinal cord developed. The development of the cells was changed by their transplantation, so their future function was dependant on their location, not on the cells themselves.

Further experiments showed that individual groups of cells ‘organise’ developing tissue into organs. Notochord cells organise development of the spinal cord, the mesoderm in the head organises development of the brain. The body begins as a cluster of undifferentiated cells, but as the cells organise themselves they influence the type of organs that cells near to them will become. The ‘organiser effect’ shows why the head always develops at the same position on an embryo, and how all the organs of the body grow in correct positions relative to one another.

Last edited: 27 August 2014 06:06